រួបរួម . UNITY

The death of former King Norodom Sihanouk on October 15, 2012, was a great loss for Cambodia.

At the end of the Rainy Season, the Cambodian people celebrate Pchum Ben, or Ancestors’ Day, a 15-day religious festival that is the most important gathering time for families. On October 15, 2012, at my countryside home in Battambang, my mother was preparing food for Buddhist monks at a nearby monastery, I was still in bed and my dad was listening to the radio. Suddenly, he came to us and said “The King Norodom Sihanouk just passed away”. My mother and I were shocked. Quietly, her eyes filled with tears and she seemed to begin praying. I was overwhelmed by silence, but felt I had to do something. I told my parents, “I have to go back to Phnom Penh”.

I went to the bus station but every bus ticket was sold out. Two days later, on October 17, 2012, I was able to find a seat, on a plastic chair in the aisle, on a bus back to Phnom Penh. At the same time, accompanied by King Norodom Sihamoni, Queen Mother Norodom Monineath and Prime Minister Hun Sen, the body of the King Father was returning from Beijing. During my 6-hour journey, I sent messages to friends informing them that I was heading to the Royal Palace. As we neared the city, traffic was gridlocked. Impatient, I asked the bus driver to let me off in the middle of the road and continued on by motorbike taxi.

When I arrived home, I immediately changed into mourning clothes: a white shirt, black trousers, a black ribbon on the left side of my chest. With one camera and one lens, I headed straight to the palace along the riverside via Sisowath Quay. The area was overflowing with the crowd, and I saw many of my friends among them. Policemen and security guards were trying to control the crowd, pushing us from place to place. I asked myself, “Where can I go to be in the best position?” Eventually, I managed to find a spot with other regular citizens near the main entrance. A few minutes later, the vehicle carrying the King Father’s royal coffin passed right in front of me. The voices of old and young people were all mixed together, praying and crying. It was tough. My heart hurt. My tears were falling uncontrollably. A friend of mine told me, “Hak, put your camera down.” But I just could not stop. I kept shooting without any preconceived story in my head.

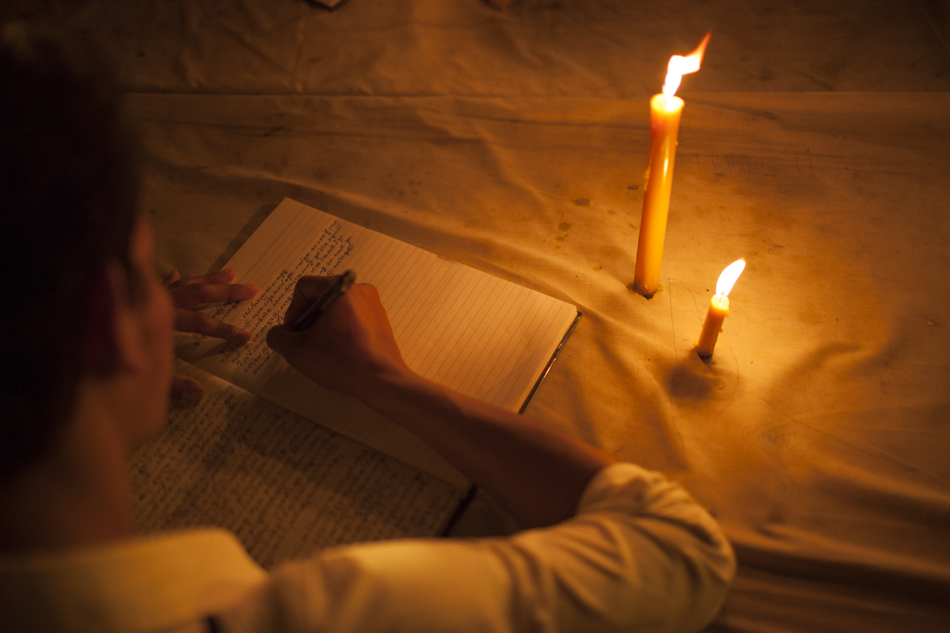

Later on, I learned that Cambodia national broadcaster TVK announced that 1.2 million people had lined the road from Phnom Penh International Airport to the palace that day. That number included myself. The royal government declared seven days of mourning from October 17 to 23, 2012. Mourners came to the palace from across the Kingdom of Cambodia to pay their respects to the King Father. Clouds of smoke from incense and candles made the palace look aflame, creating an atmosphere of spiritual mystery. Buddhism is the state religion of the kingdom and the King Father himself was Buddhist, so the mourning practices followed Buddhist tradition. In Buddhism, monks and nuns shave their heads on holy days as an offering to the Buddha. On this occasion, mourners shaved their heads as offerings along with lotuses and jasmines.

On October 20, 2012, a remarkable thing happened: without prior planning, over 5,000 Buddhist monks came together in front of the palace for meditation and chanting. The palace became a place of pilgrimage, not just for prayers for the King Father’s soul but also for peace in Cambodia and across the whole world. Rain fell like a heavenly blessing under which people kept gathering and chanting.

A cremation building was constructed very quickly, in less than two and a half months and beautifully in traditional Khmer style. The King Father’s body remained inside the palace for three months before the official royal cremation ceremony, held February 1 – 7, 2013. When the flames touched the King Father’s body at 6.30PM, on February 4, 2013, I raised my hands above my head in a final show of respect as his last song, “Goodbye Cambodia,” played.

“Unity”, is dedicated with love and respect to the King Father, the royal family and my fellow citizens. Alongside my fellow citizens, I was there, capturing what was happening around me, this important part of the nation and history of the Kingdom of Cambodia. I want people to see what I saw and feel what I felt.

Phnom Penh, 2012 – 2013