Alive

I started this long-term project “Alive” from my own family’s memory. From there, I decided to expand this project to other families living inside Cambodia and then Cambodian diasporas who left their homeland to live at different parts of the world after the post conflict/ war, by using photography as a means to capture the memory of human history. Now, it is a race against the clock because living witnesses are gradually disappearing.

40 years after the Khmer Rouge war, the old people began to die. If all these living witnesses of the war pass away, with their experiences undocumented, those memories will be lost. Without learning from the past, we wills repeat old mistakes. This is important not just for Cambodians but for all of humanity.

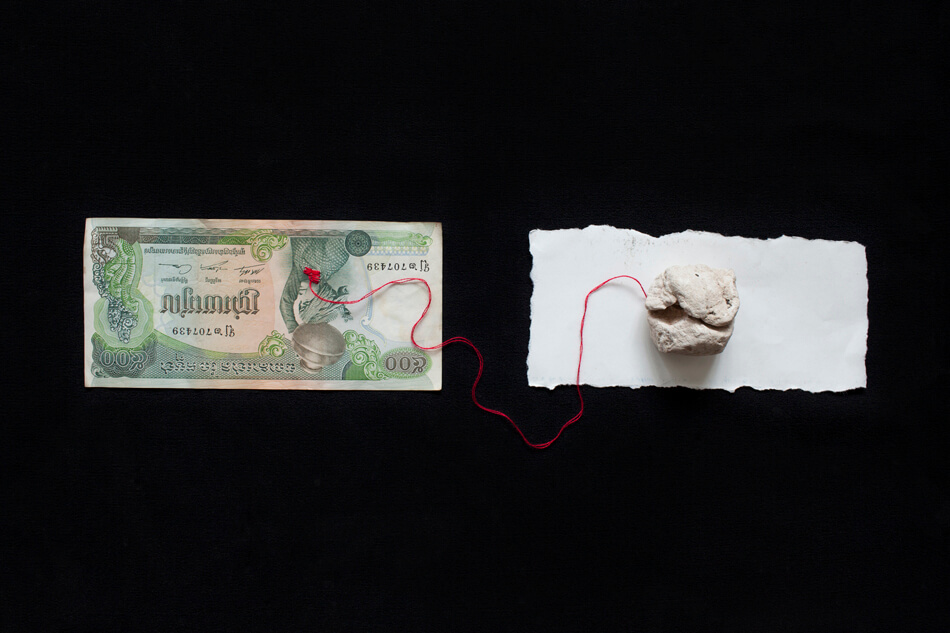

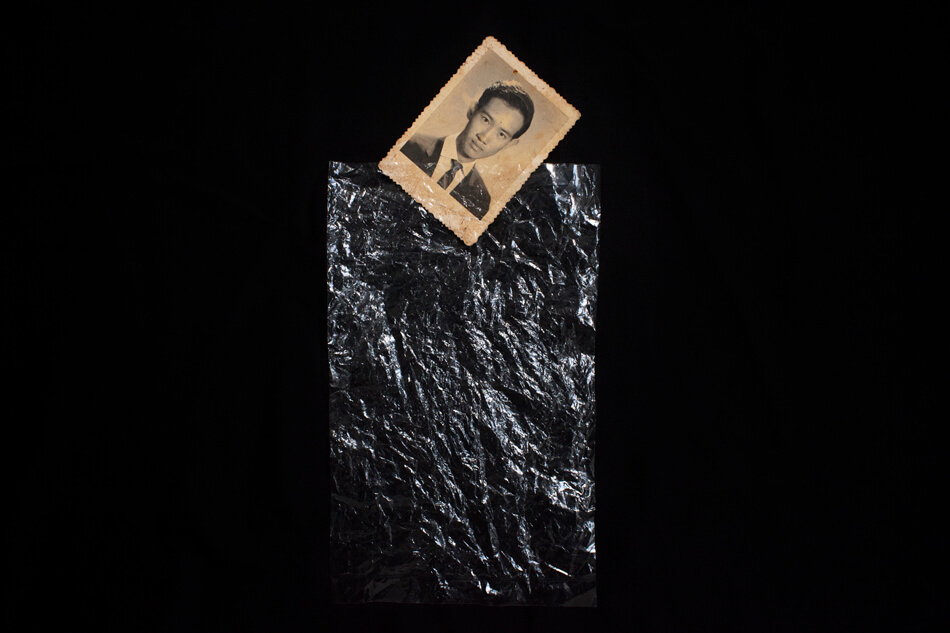

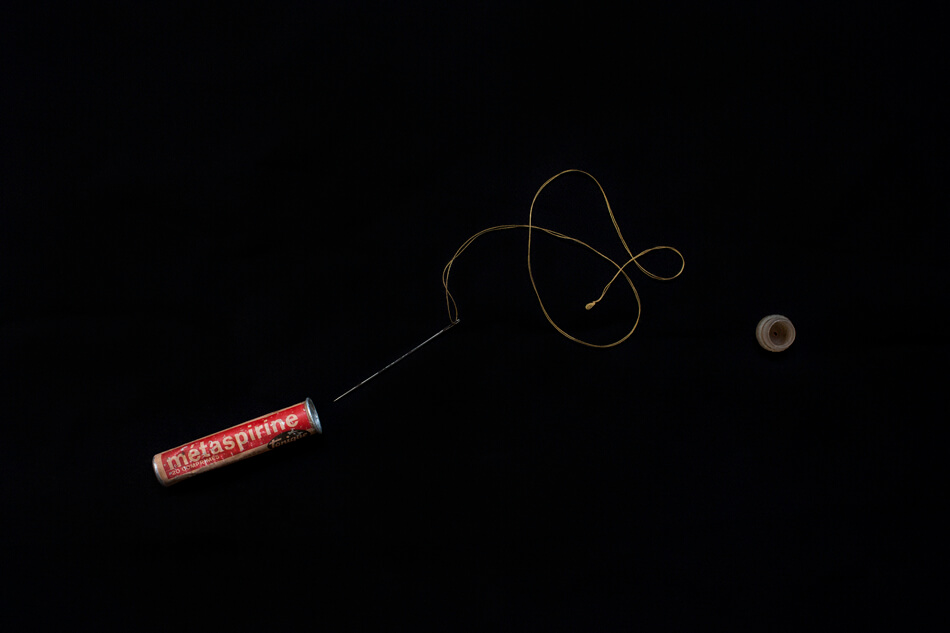

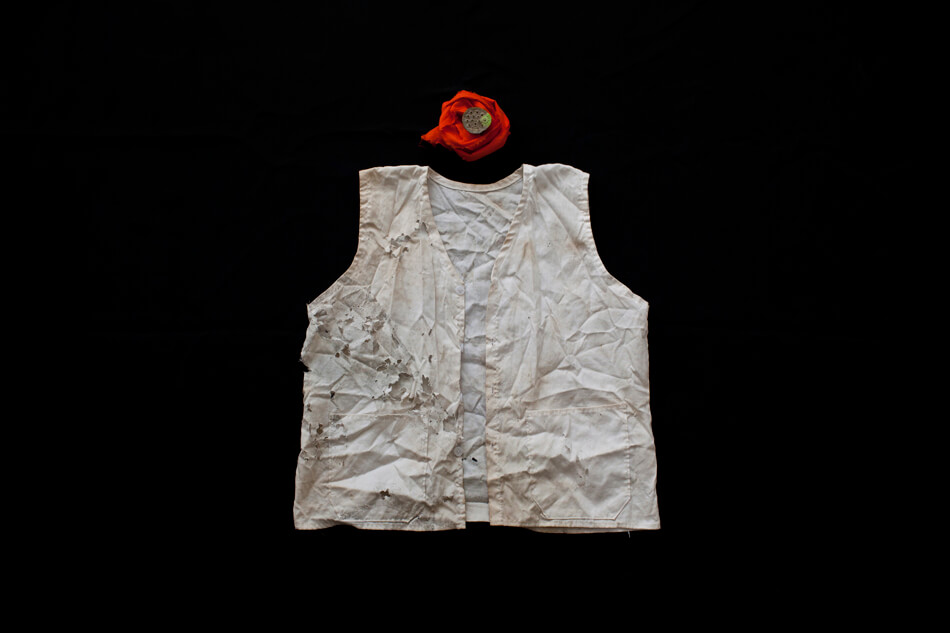

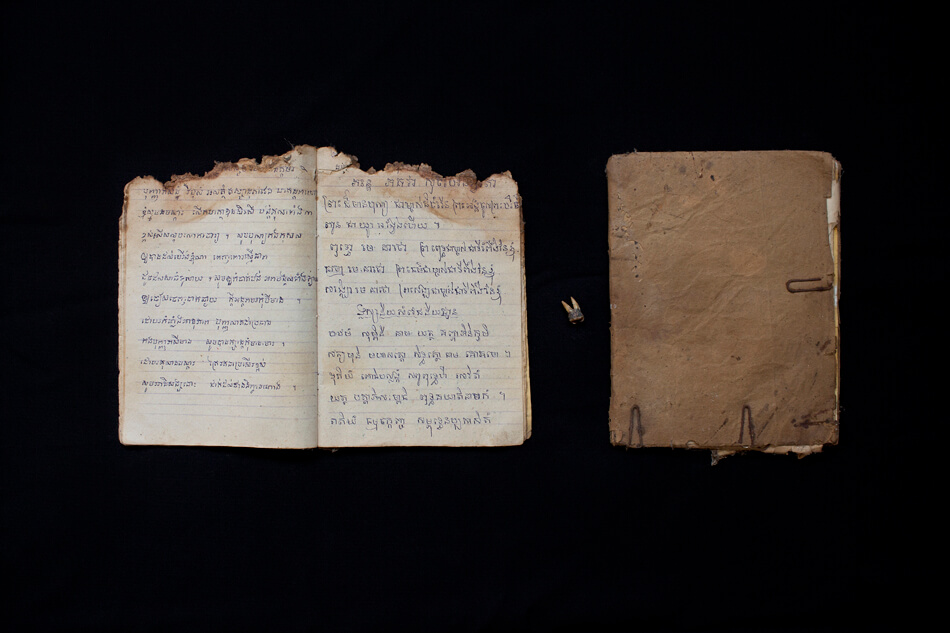

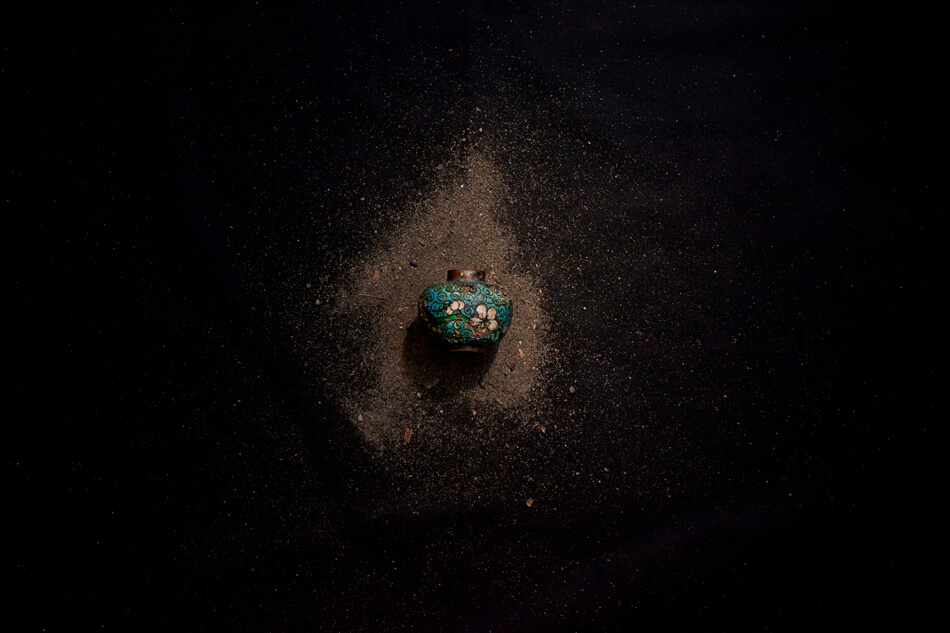

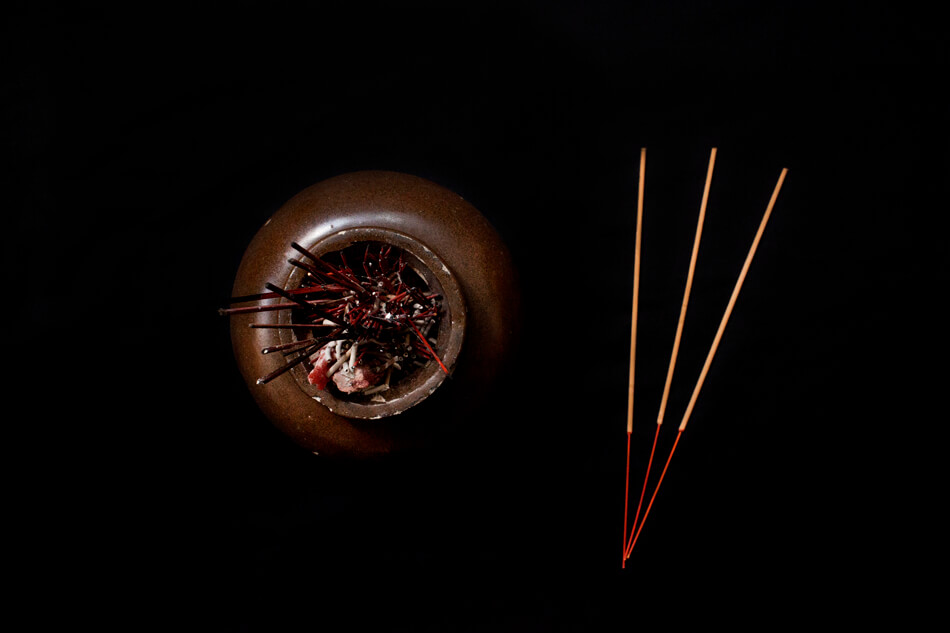

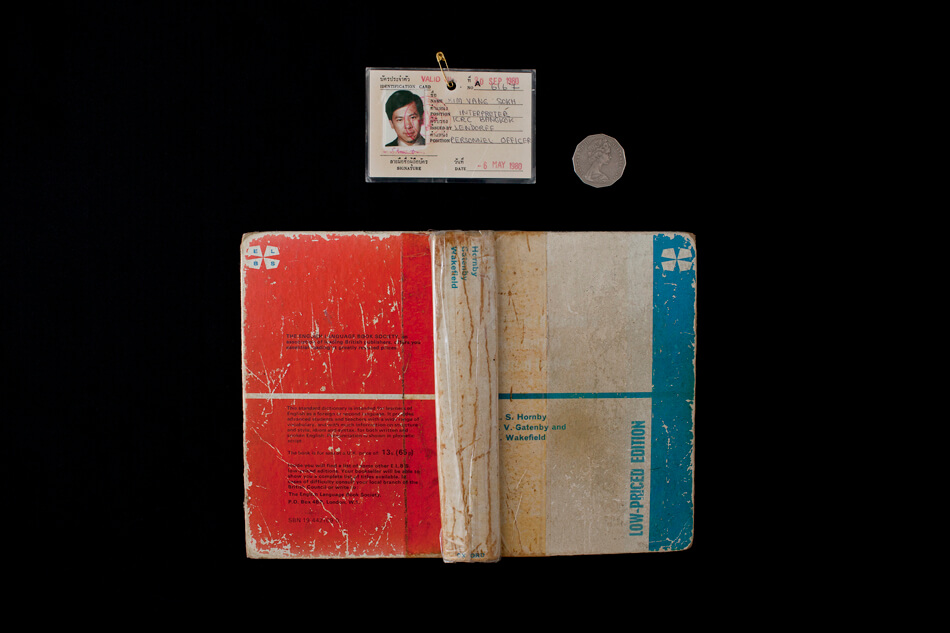

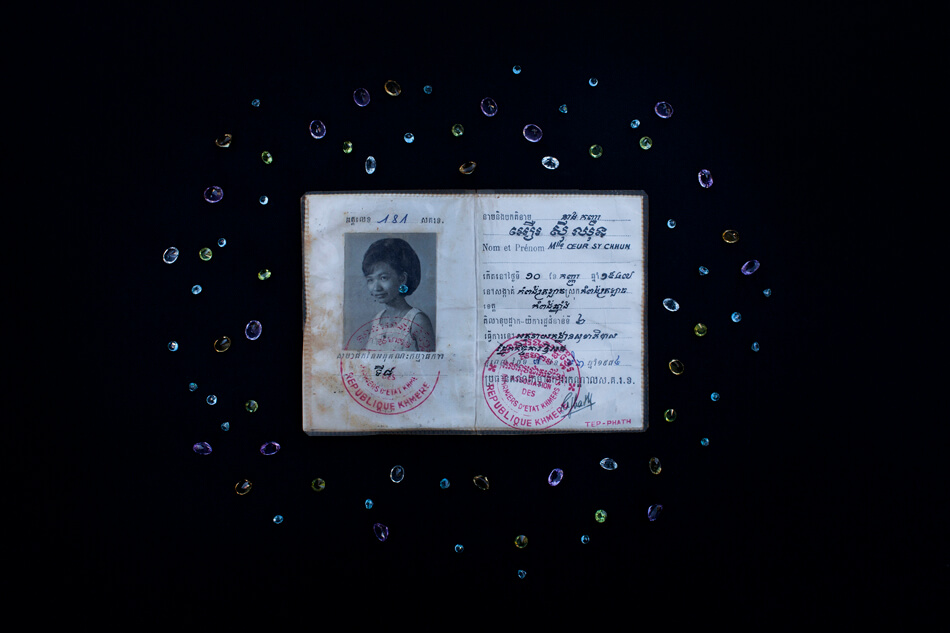

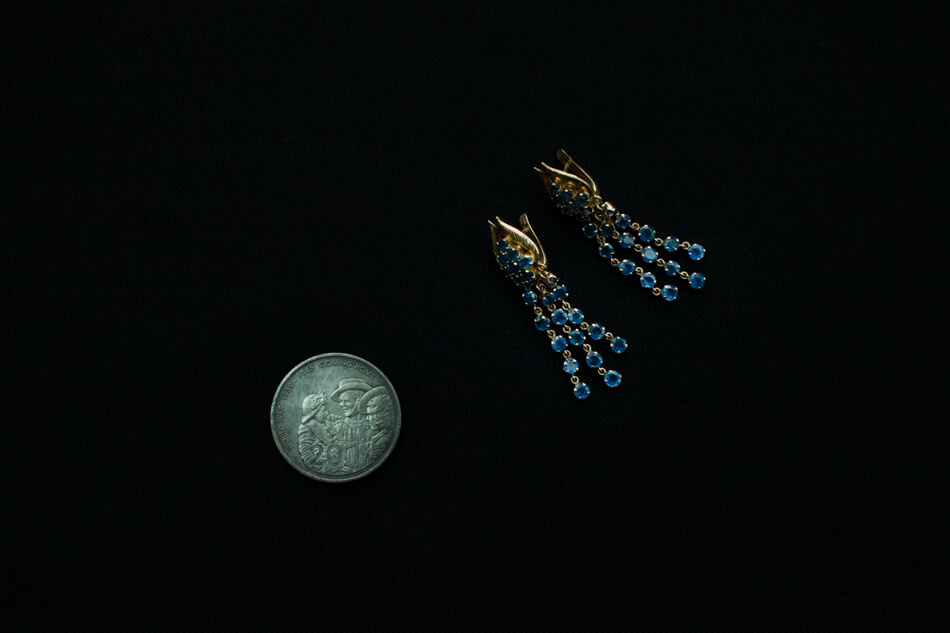

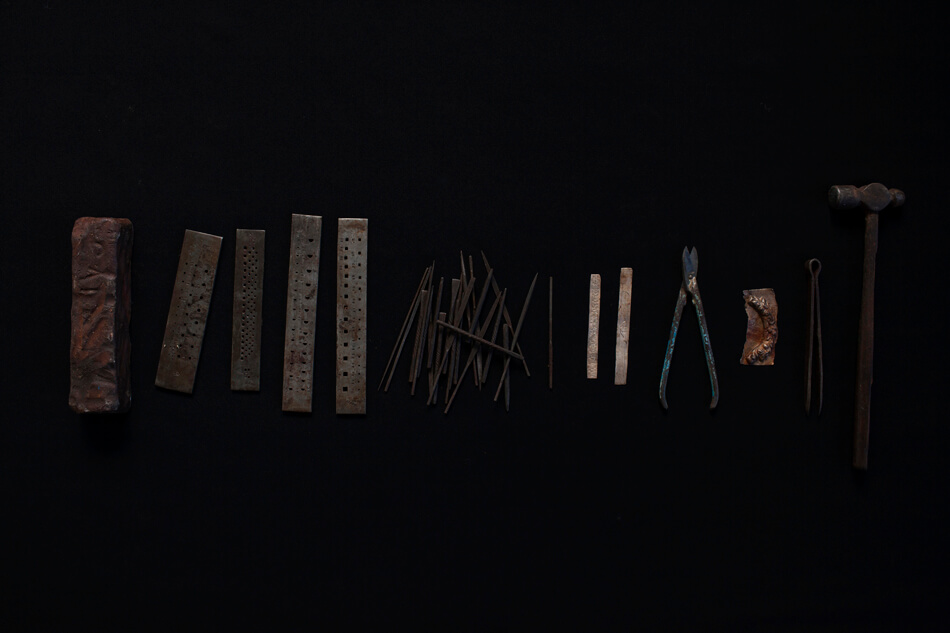

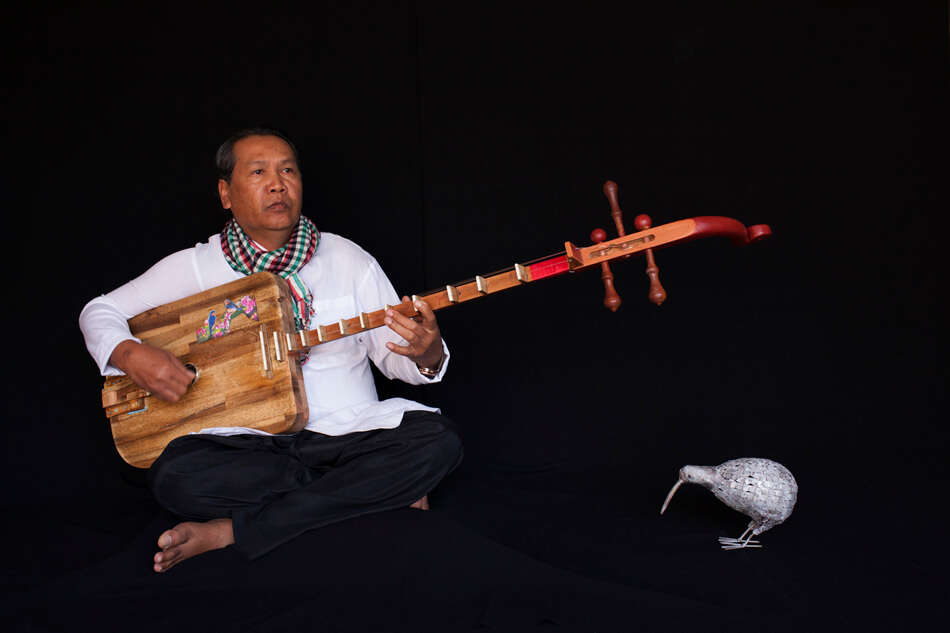

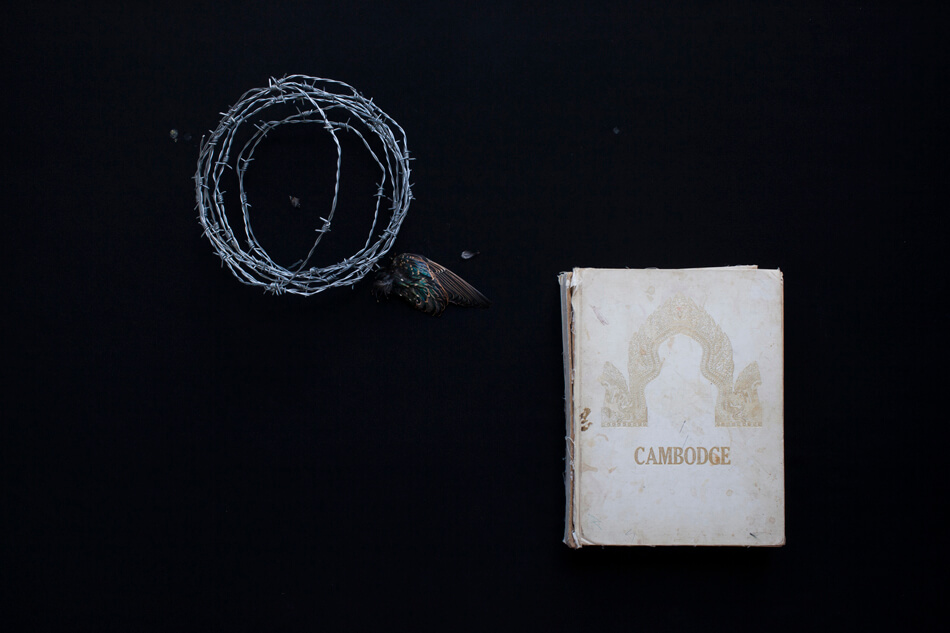

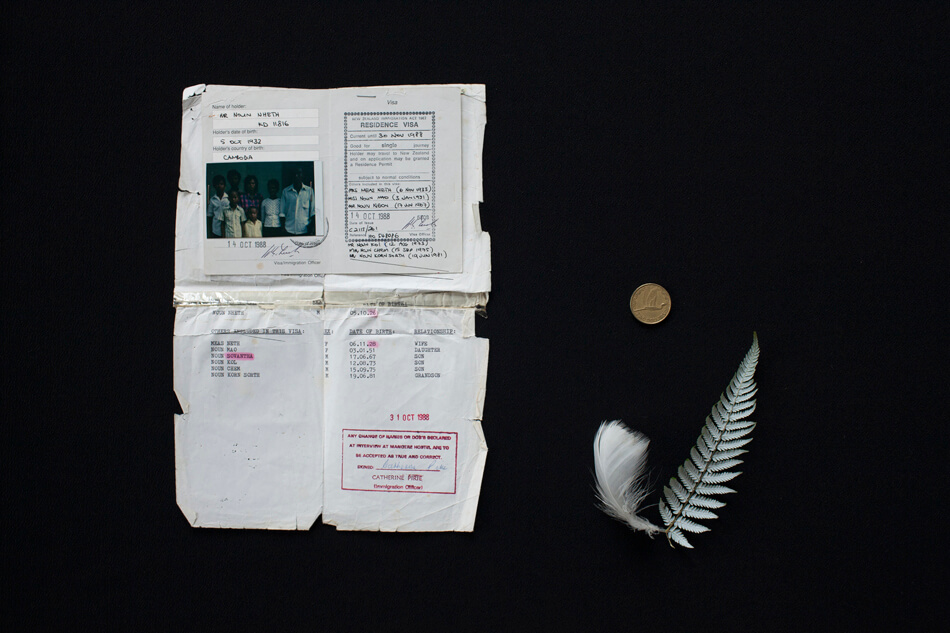

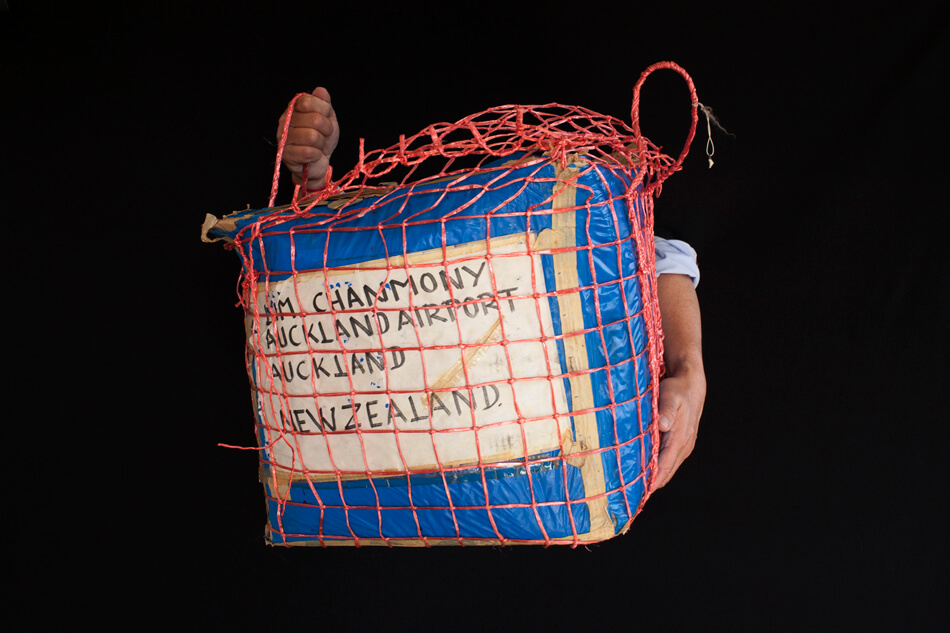

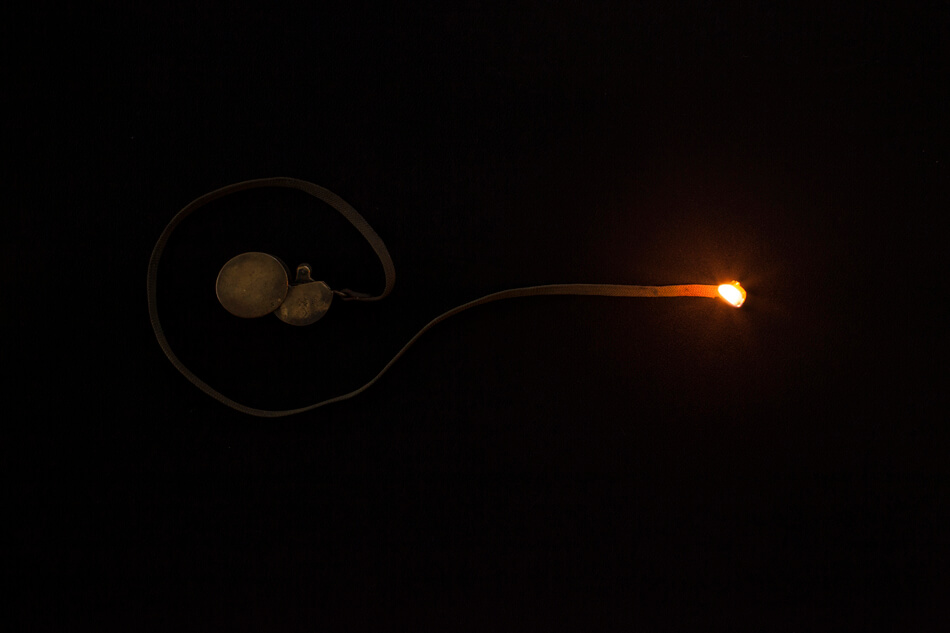

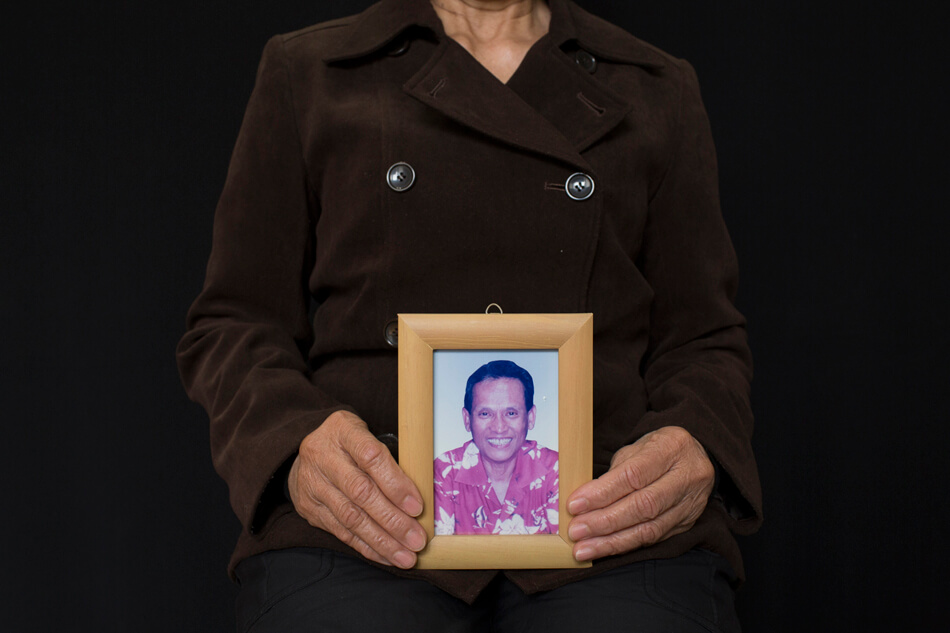

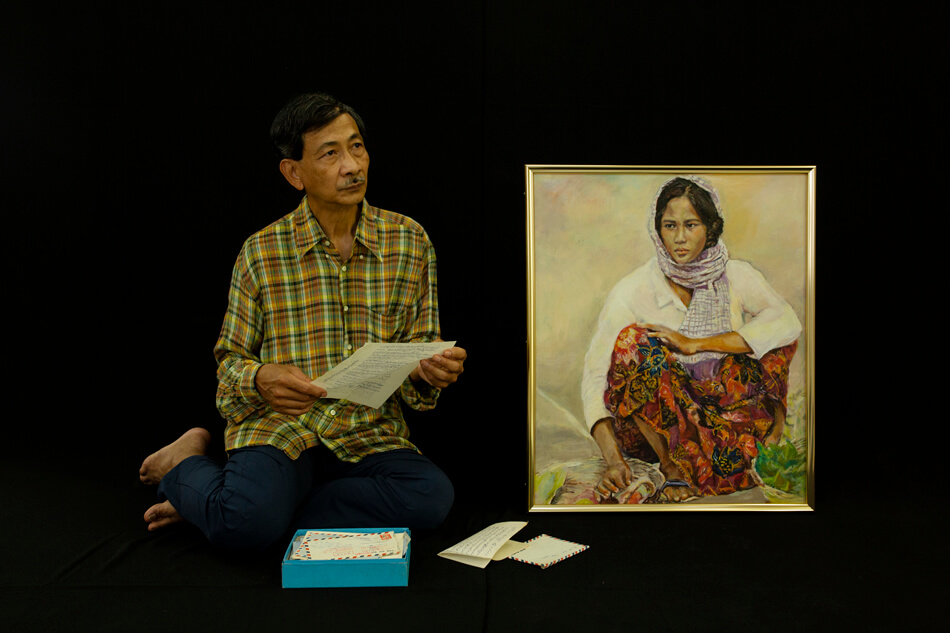

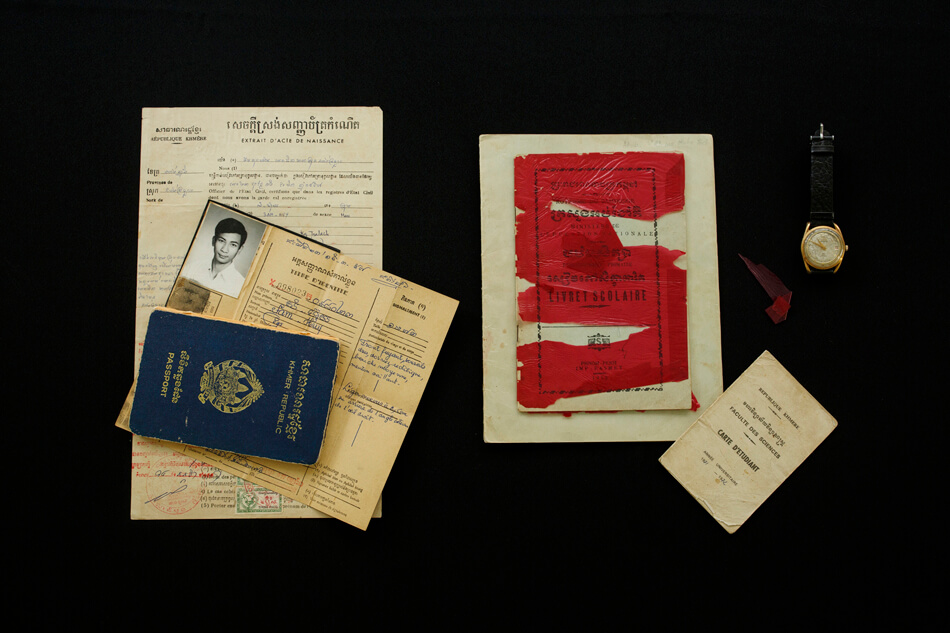

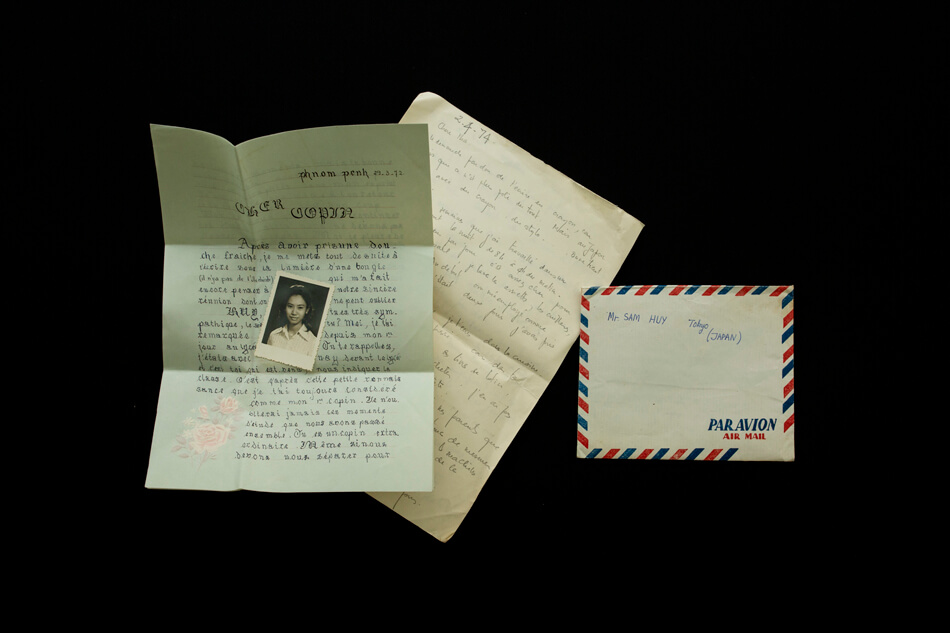

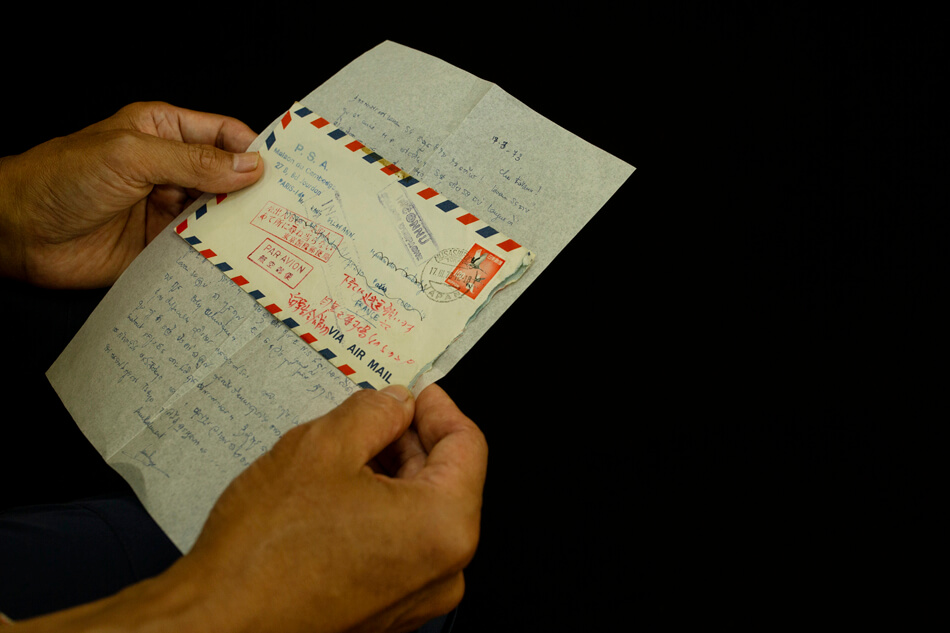

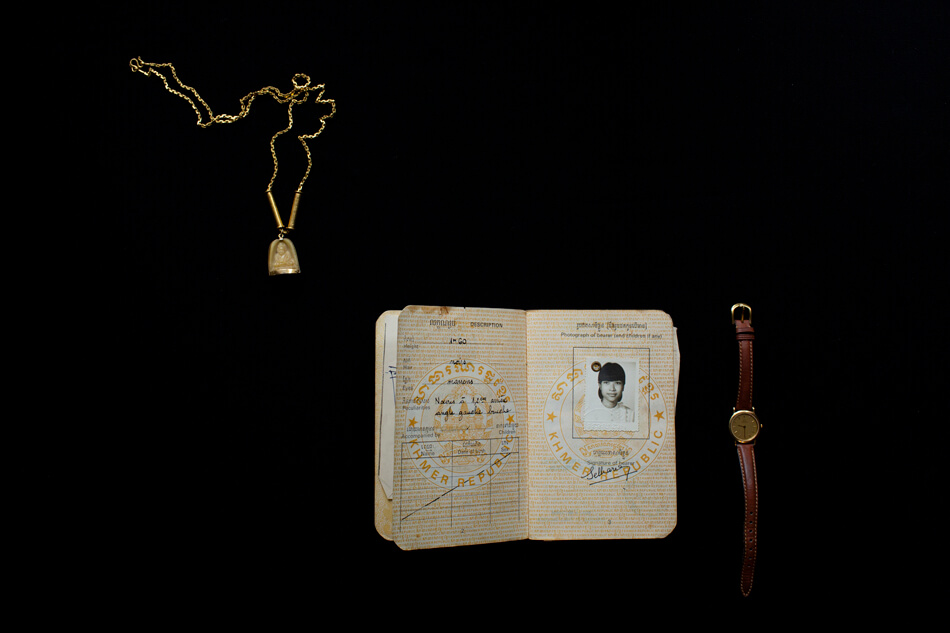

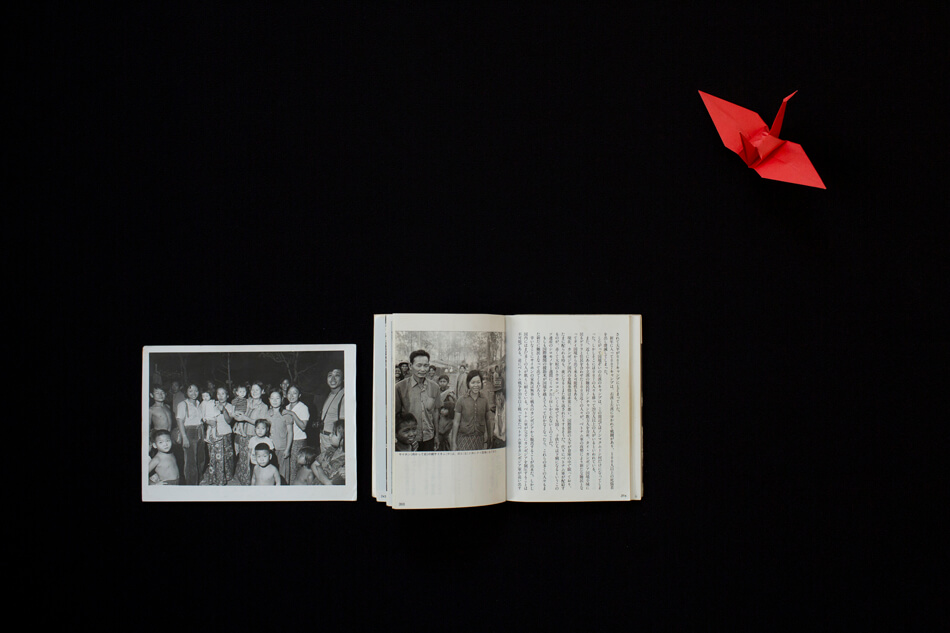

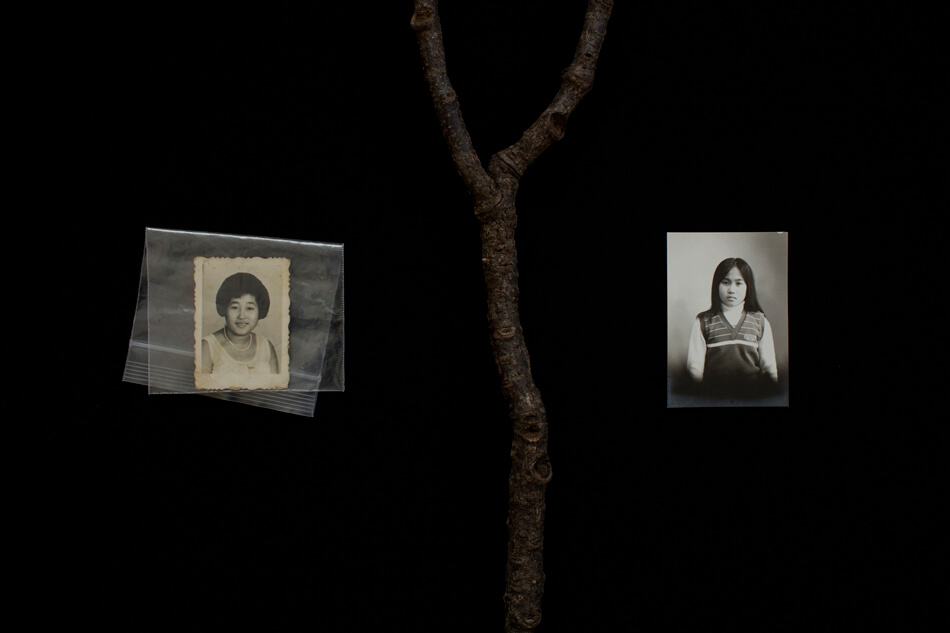

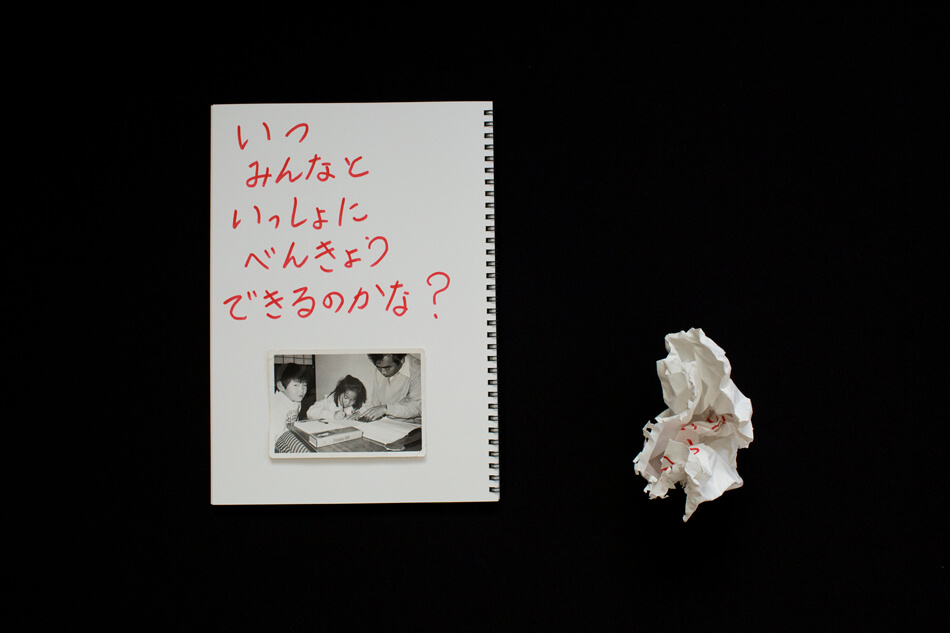

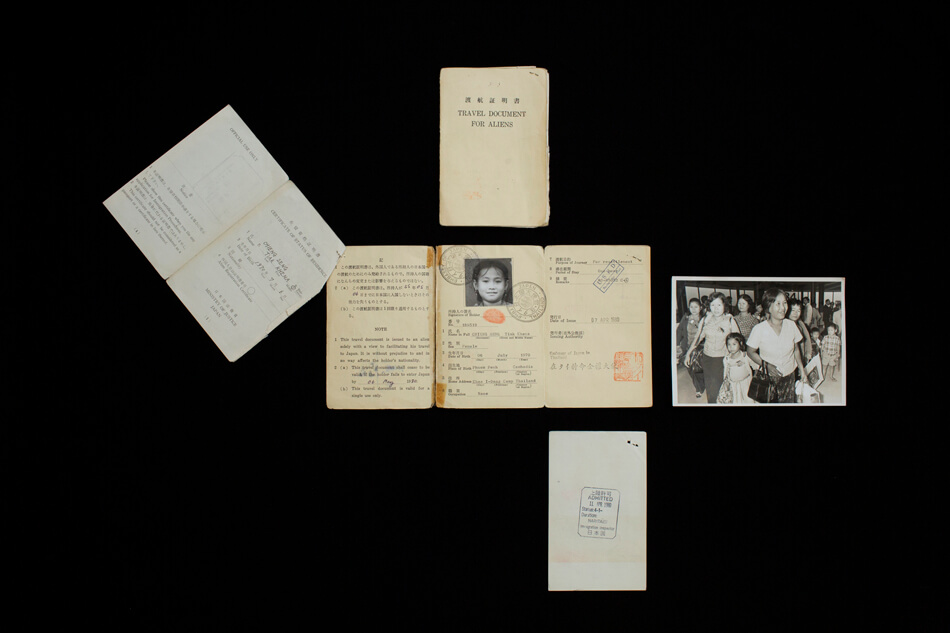

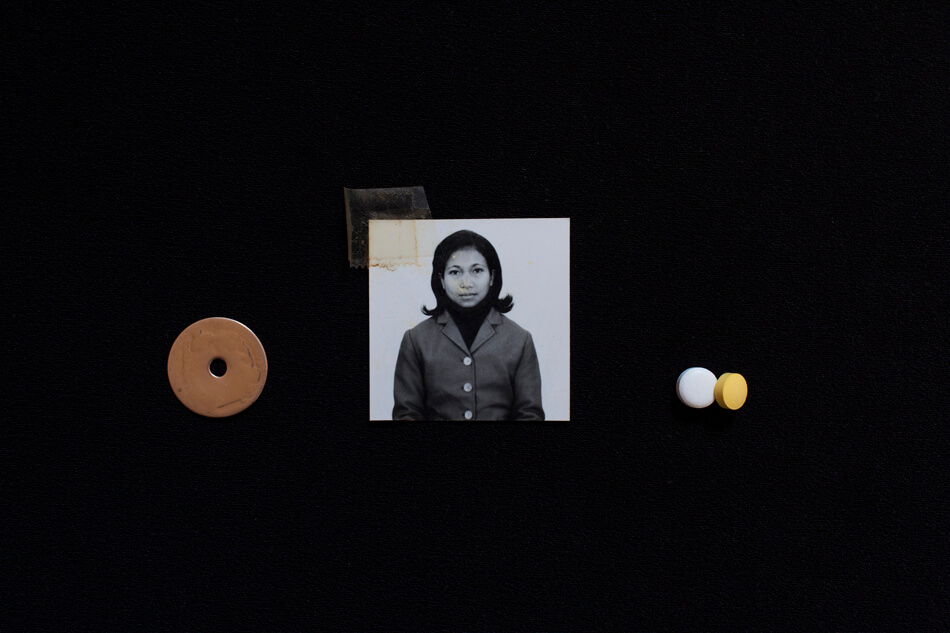

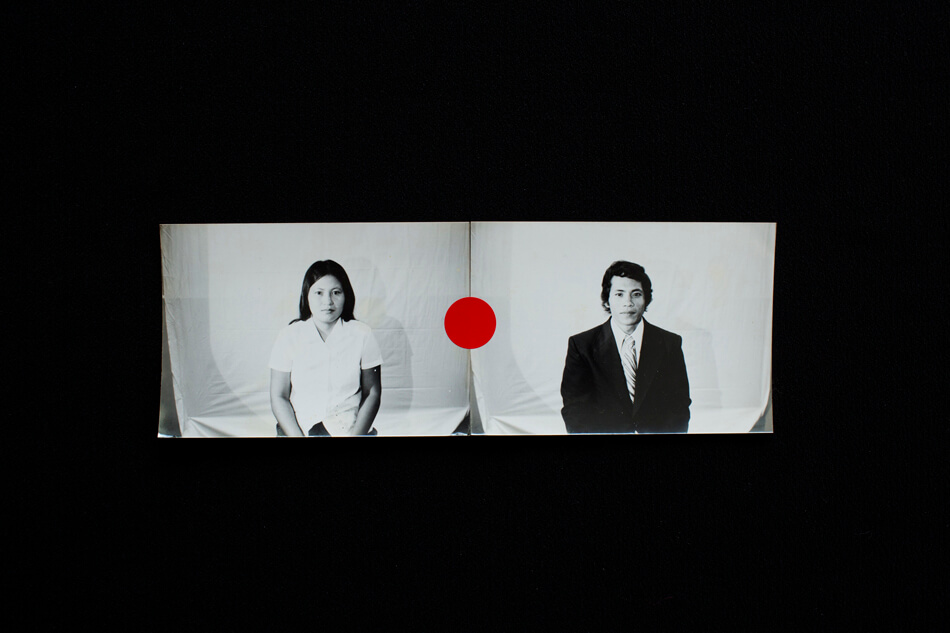

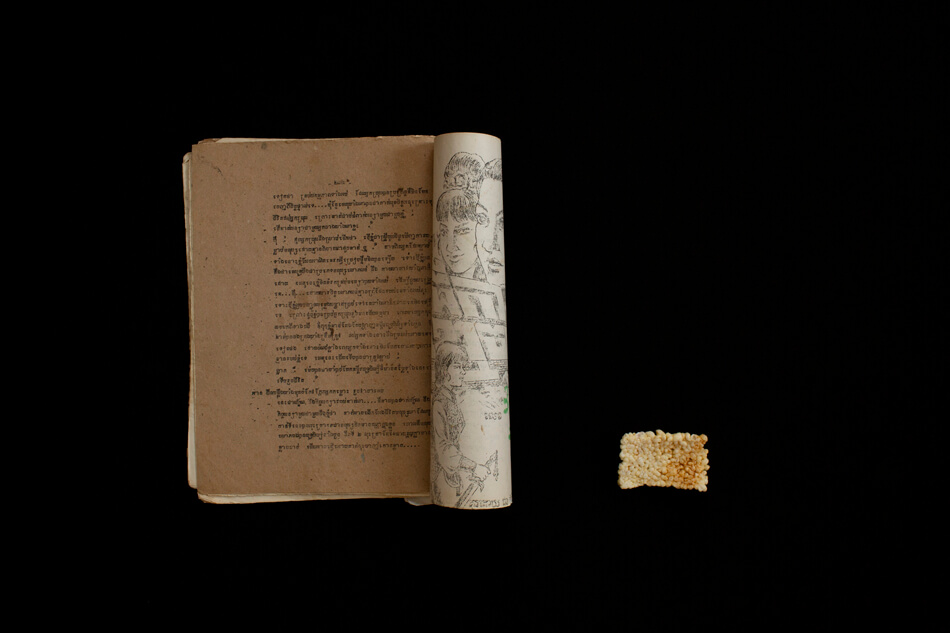

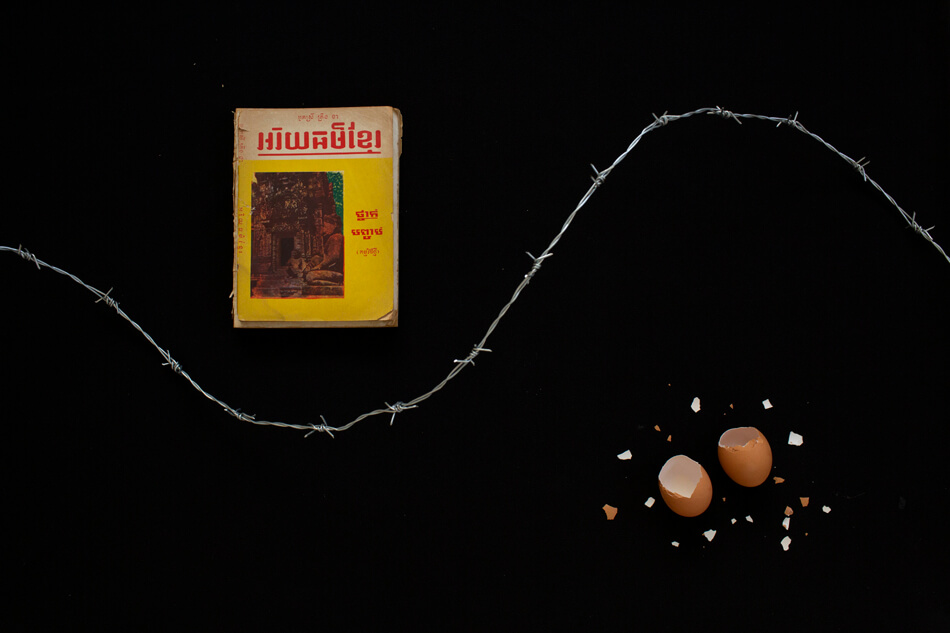

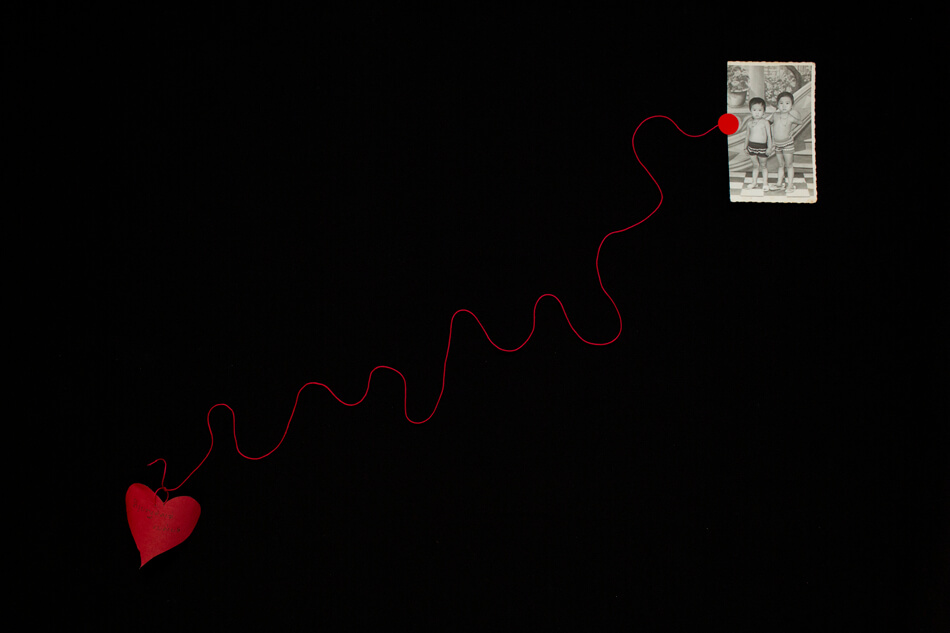

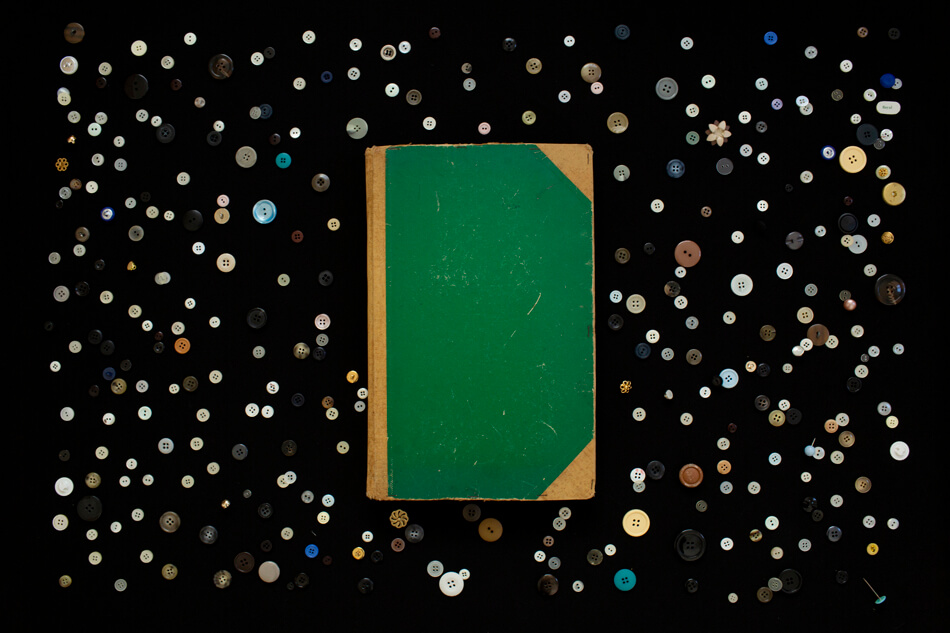

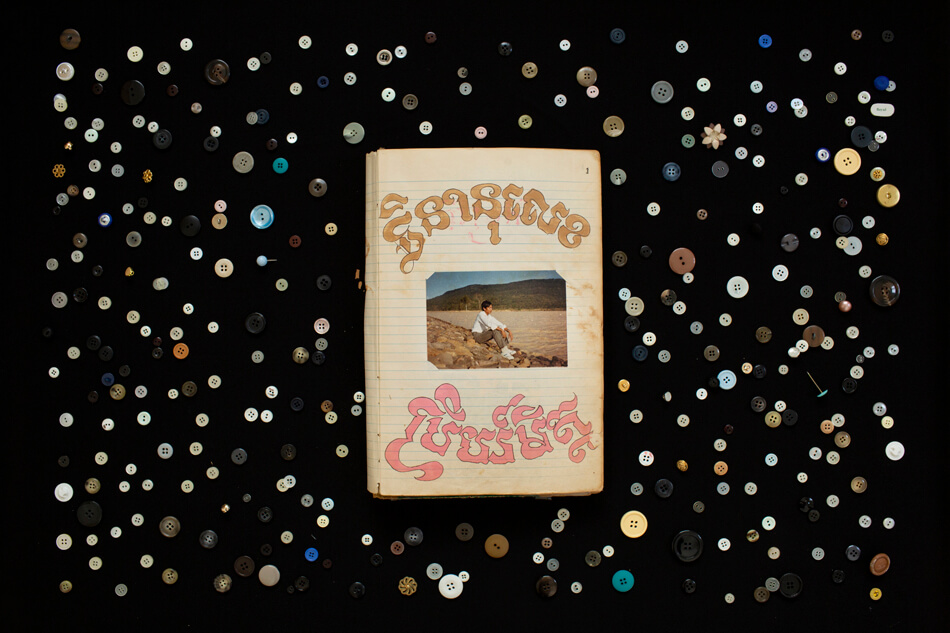

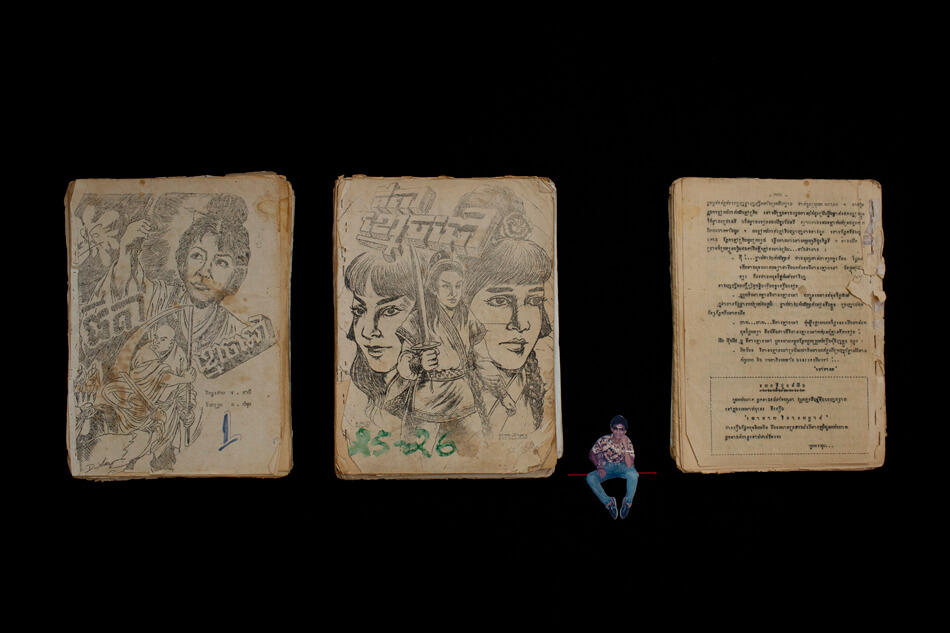

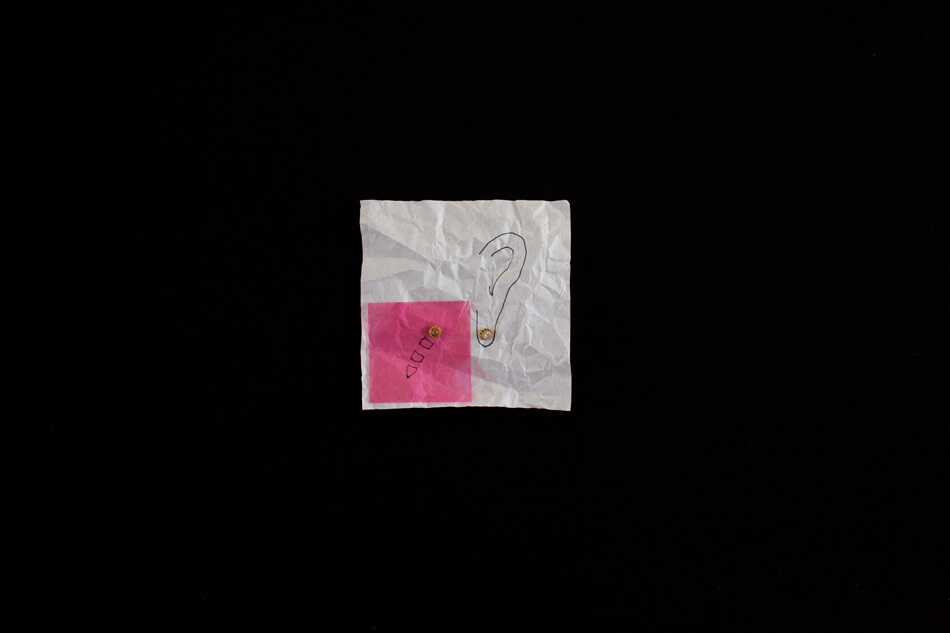

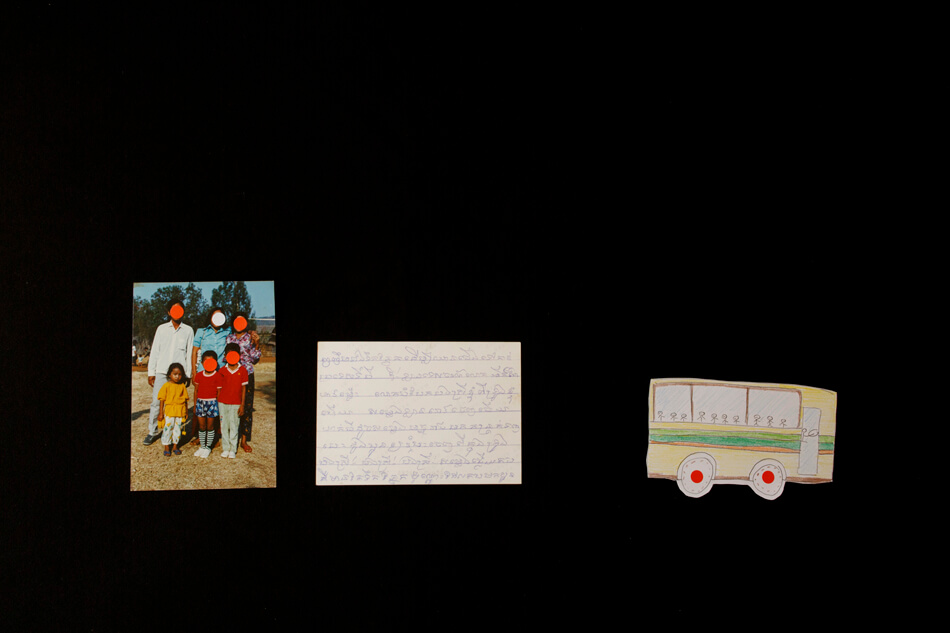

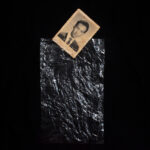

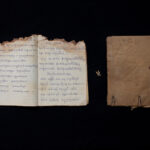

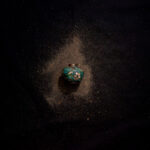

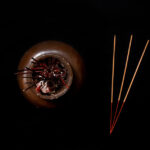

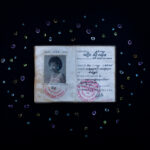

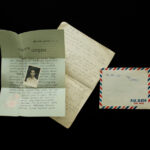

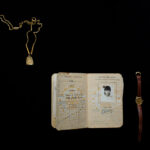

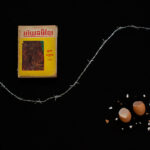

Most of the objects featured in my photography have been used by families before the war, during the Khmer Rouge regime, at the border camps, and then travelled on a long journey with the victims and survivors to new lands and continued to be used as everyday items. Each photograph has a clue that leads to a true story behind each individual object. The objects have been reclaimed, digging them out of the dirty land after the Pol Pot period, or they have been kept throughout the families’ lives.

All these photographs and objects are deeply significant. They are evidence of a past time in history. War can kill victims, but it cannot kill the memories of the survivors. The memories should continue to be alive, known and shared in the current consciousness of human beings, and the preservation of heritage for the next generations.

Chapter I: Battambang – Cambodia (2014)

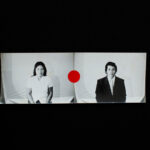

On April 17th, 1975, the day of the fall of the Lon Nol government in Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh and ordered the city’s two million residents into the countryside. People were able to take only a few of their belonging. They often only carried clothes, cooking utensils, a few pieces of jewellery and above all, photographs in order to remember the loved ones. To hide their previous background, my parents, as well as other families, threw away many old photographs and identity cards. Otherwise, they would have been killed immediately if even one Khmer Rouge soldier found out who they were, especially if they were well-educated people (intellectuals), former government employees or former army officers. Leaving their homes, they left many things behind. Even keeping their photographs to remember their previous lives was a huge risk. One day, I discovered something that I didn’t know before. I thought that my parents had simply hidden their photographs in their clothes. Reality was more poignant! All photographs had been covered in plastic and buried under the ground at the place where they stayed during the regime. Time and time again, they went discretely to check if these precious fragments of their past life were still there.

I was born in Cambodia two years after the fall of Khmer Rouge regime, during the period in which everything lost was being revived and rebuilt, I grew up listening to the memories of suffering and painful experiences of the survivors of the regime. Slowly, stories of the war began to affect me. The scars of the conflict are reflected in my photography. Looking at the photographs that had survived this period, I became fascinated realising that photography is one of the main ways in which our history is documented.

Chapter II: Brisbane – Australia (2015) – Supported by Arts Queensland

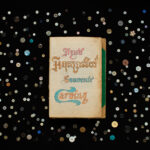

I have engaged with 4 Cambodian diaspora families living in Logan/ Brisbane, I was still fascinated with the objects and photos which migrants brought along with them to Australia, especially from the border camps in the 70s and 80s.

I was my first time to extend this project outside of Cambodia.

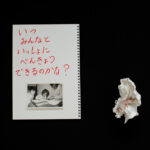

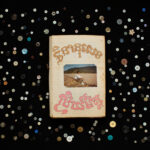

Chapter III: Auckland – New Zealand (2018) – Supported by Rei Foundation Limited

I questioned myself: “Why do I keep working on this project?”

War breaks things to pieces, not only the landscapes of one country, but also humanity. I have been trying to collect all of these broken pieces of memories of Cambodian diasporas to put them back into one. It is a healing process for both the old and young generations. It brings us a lot of conversation.

I have produced a body of work that engaged with 12 Cambodian families now in Aotearoa, documenting personal objects that hold meaning as a part of their journey in surviving the Khmer Rouge and refugee camps and then resettling far from their homeland. By sharing the experiences of these former refugees through photographs and text, we aimed to generate new dialogues between individuals, whānau and communities to remember, (re)acknowledge and (re)analyse personal and national histories and identities.

Chapter IV: Tokyo, Kanagawa & Saitama – Japan (2020) – Supported by The Japan Foundation

The Khmer Rouge regime brought psychological crisis to people across many generations. Both victims who experienced the regime directly, and the former scholarship students who left Cambodia to study abroad before the regime and got stuck overseas by war/conflict, are affected by psychological crisis. Some faced and experienced the conflict directly, some heard about it from others, and some did research on it later after the end of the regime. But all of them have lost family members through executions and separations. The students stuck overseas lived without hearing any news from their families for several years. I have produced a body of work that engaged with 13 Cambodian families now in Japan. The effects may show themselves in different ways, but they all are victims, victims of history. And of course, the regime has affected the children born post-conflict as well. It will take decades to heal.

REMARK:

“ALIVE” is a long-term and on-going project, which I will continue to work with Cambodian diasporas/ communities who living in Europe, The United States and Canada. The main goal of this important project is for for photo book publication.